Odyssey 5.228-326

Is it a man on a raft, or the man on a raft; or is it this man, long-suffering Odysseus, adrift on a raft on the wilful, monstrous, god-driven ocean, or Man—mankind—on a raft of his own artifice riding upon the turbulence and violence of nature? The Odyssey may intend all four, but I don’t think the last one is quite right, as temptingly romantic and bleak as it is. I can’t help but feel that there is something masculine about Homer’s image. The opening word of the poem, ἄνδρα, is decidedly male. But all the same, that picture, of Odysseus braving the stormy sea on a raft, is iconic in the world’s imagination, like the astronauts’ photo of earthrise over the moon, or the crucifix. Penelope at her loom weaving and unpicking a web to keep her options open, by contrast, seems decidedly feminine, but equally tempting to see as an image of Man’s situation. The same word, ἱστός, a thing stood upright, is translated either mast or loom in context.

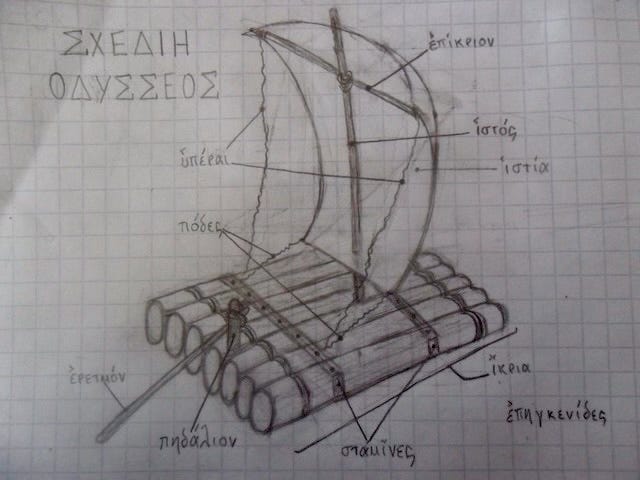

Much of the present passage is descriptive narrative, Homer going solo rather than filling his mask with speeches or dialogue. He positively immerses in the building of the raft; one feels the connections between segments of his crafted hexameters like the morticing of Odysseus’ craft. I wrote the following in my first book:

… the works of art represented within the Odyssey itself bespeak an aesthetic of construction, wholeness, unity, form, and function. Three wondrous artefacts buttress the story: Penelope’s web, Odysseus’ raft, and the couple’s marriage bed of denatured olive. All three depend upon a frame: all three must therefore be conceived at some level as wholes before they are executed. All three involve transformations of various kinds—from vertical to horizontal (web to shroud, trees to planks, trunk to bed); from raw material to finished, humanly purposive artefact. All three are unadorned: they are each perfect marriages of form and function.

By contrast again, the art works represented in the Iliad point to a different aesthetic. Two exemplars come to mind. Helen’s web (3.125–8) is a Bayeux Tapestry; episodes of the struggle between the Achaeans and the Trojans on her account appear to be embroidered (ἐμπάσσειν) upon a web already woven. In the case of the great shield as well, the artwork is an adornment, superadded upon a highly functional implement. One is made to feel this rather vividly when the shield is penetrated by Aeneas’ spear. A nightmare for the art crowd. In the distinction between art as a perfect marriage of form and purpose, and art as an adornment superadded, gracing the necessary and the useful, and perhaps also transforming them, I believe we have as real a distinction as can be made between the aesthetic sensibilities of the poet of the Odyssey and the poet of the Iliad. Achilles’ lyre is extravagantly silver-bridged; Demodocus’ lyre is merely—and resonantly—hollow.1

Homer’s evocation of the storm is also vocal miming, of a bravura kind. One thinks of King Lear’s storm. Much energy is often spent on visual and sonic effects in the staging of that play; but just as in Homer, the storm comes to torrential life in the consonants, vowels, and rhythms of the poet’s words. The performer’s breath is the breath of the four winds.

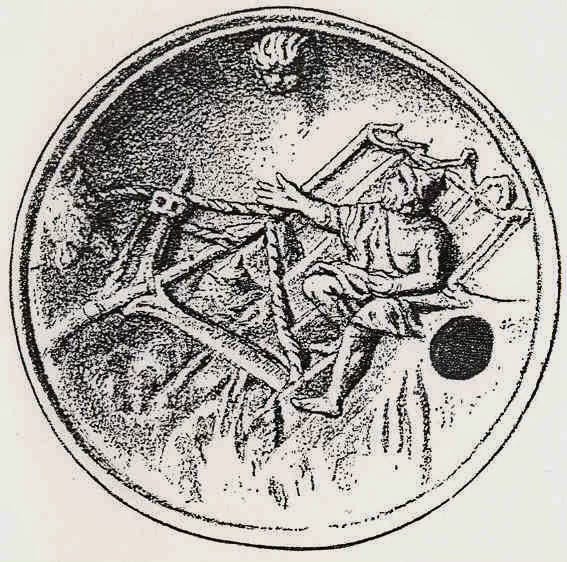

The consummation of the vision, to my mind, comes from the god’s view. The gods are Homer’s genius and his arsenal. Poseidon is returning from his festival in the land of the Aethiopians, and spots the little man on the limitless sea. Boy is he pissed! Mostly, it seems, at the other gods going behind his back. But one cannot but feel the visceral venal energy of the jealous sibling, stumbling on his useless brother’s turreted sandcastle, and kicking it to oblivion. From the distance the god’s-eye-view gives us, Odysseus’ vessel of tall trees’ timber proudly jointed, becomes a speck, a tumbleweed upon the immense briny swell. He himself becomes a no-man. Calypso’s pines become toothpicks, Odysseus’ days’ long labour and shipwright’s engineering, so much broken Lego™ and wasted hexameter verses.

As flies to wanton boys are we to th’ gods;

They kill us for their sport.

In Greek:

A. P. David, The Dance of the Muses: Choral Theory and Ancient Greek Poetics, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006, 180-1.

Man on a Raft: Homer in English