Odyssey 4.742-847

Homer compares Penelope’s state of mind, before she falls asleep, to that of a male lion encircled craftily by huntsmen; her thoughts start, it would seem, like the lion’s feints at the men’s shifting perimeter. The comparison of Penelope’s mind to the lion’s is not the last cross-dressed simile in the Odyssey. We shall note them! Do such similes bear with them a claim or a thesis? That the natures and experiences of the sexes can be compared in such a way as to bring insight and truth? Strange, then, that the famous similes of the Iliad do not explore this transgressive technique. Such cross-comparisons are Odyssean territory.

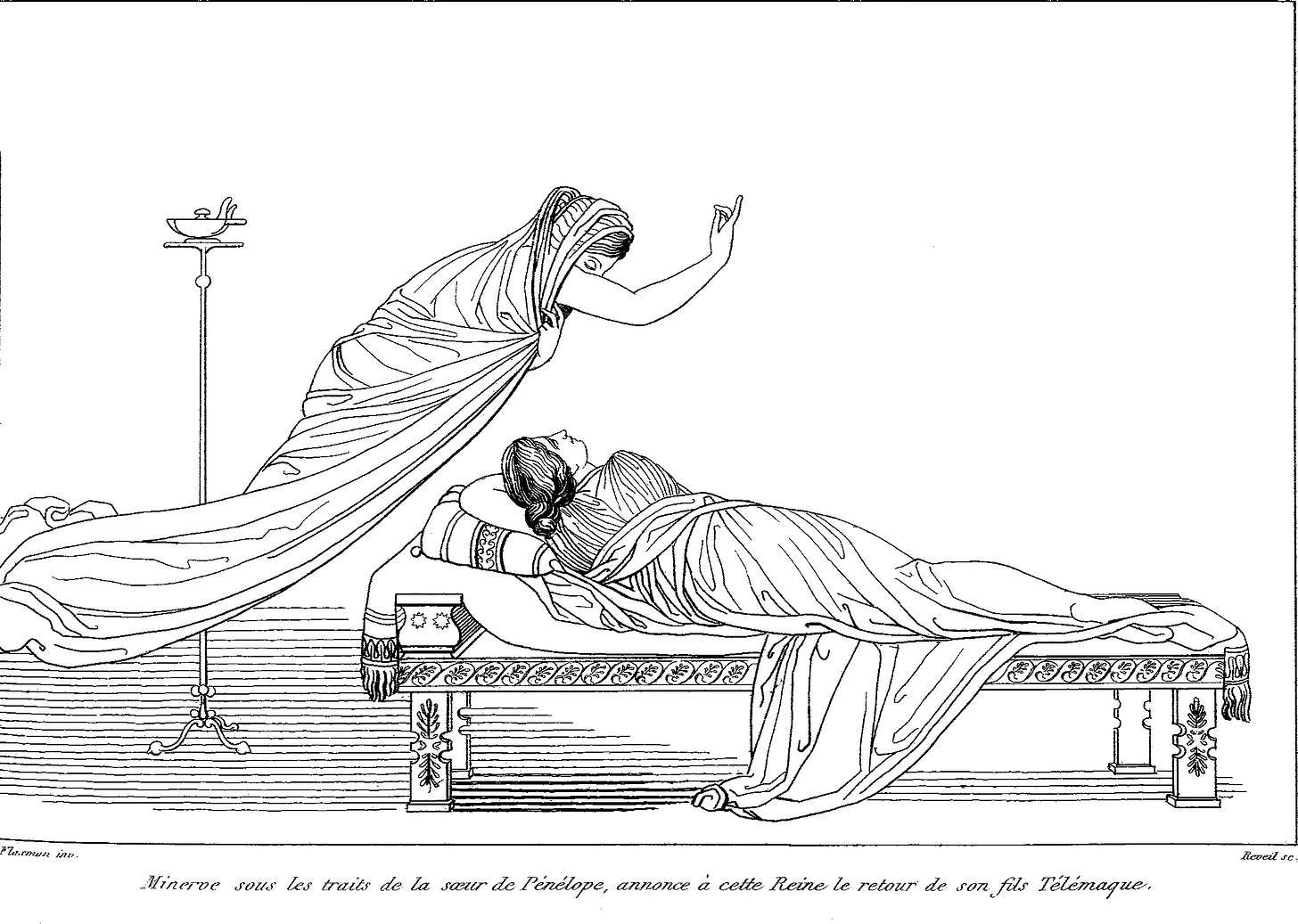

To ease her mind Athena sends Penelope a phantom in the shape of her sister Iphthime, long since married and moved far away. We are not troubled by the impossibility of ghostly emissaries who can slip through door latches, be conscious and engage in meaningful conversation, and still look like the human beings they’re supposed to be. Art makes ‘AI’ look like a joke. Athena does such things, as Iphthime says, “because she can!” We indulge this storyteller the power of his wand.

But her reassuring apparition rather makes me focus on what is truly impossible: that Penelope can somehow turn to her own sister in her grief and anxiety. Women, at least of a certain class it seems, do not move, except when they are transported to their wedding and the household they will join and preside over. That is, such women are born, move once forever away, and then become fixed local features of the earth. Helen, by contrast, is the woman who moves, and in so doing becomes the cause of war, separation, chaos, and bereavement. Penelope is only the first of the high-born women in the Odyssey who stays put, and when she appears, she descends and stands by a pillar, like an immovable axis. Calypso the nymph, Odysseus’ concealer, is the daughter of Atlas himself, the Titan who holds the very pillars that keep apart the earth and the heaven. Such pillars, of course, connect the two of them as well.

Once again I am confronted by the predicament of women. I do not suggest that Homer has an agenda other than being a telling observer in his way of telling the tale. But it does seem extraordinarily poignant that so intimate a companionship as that between childhood sisters, something I have had the joy to observe in my mother and daughters, is a companionship routinely sacrificed without acknowledgment in Homer’s society, except perhaps by Homer. Loss and separation are clearly not uniquely feminine experiences, but the appearance of her sister must take Penelope back to the time when they both were unmarried, and ‘besties’, as they say; everything on Penelope’s mind now causing her unbearable pain, both her husband and the son they produced, can perhaps still seem to lie in the future, while she is in her sister’s company. This is a way in which the appearance of Iphthime can be construed to be a Freudian wish-fulfilment by way of the gates of dream. The relief that Iphthime brings her, I would suggest, is not only by her presence, or the opportunity it gives Penelope to vent her frustrations—roundly taken, replete with a repeat of her anguished, circumflected, tonal motif—but also the fulfilled wish of the unthinkable thing, that she is virgin again with neither husband to mourn nor foolish son to fret over.

And that is not such an outlandish state of mind for her to be in. Nurse Eurycleia tells her to bathe and freshen up, and Penelope obeys. Eurycleia says, wishfully, “somewhere there will still be one who can keep / The house of the lofty roof, and in the distance the fatting farms.” It is not altogether clear who this mysterious saviour will be. There’s plenty of suitors! A principal motive of Telemachus’ secrecy about his voyage was supposed to be to prevent Penelope from weeping, and thereby marring her beauty. It would seem that both these members of the household see Penelope’s thirty-something comeliness as a bit of an asset in their predicament—which needs to be preserved. Penelope herself asks her sister about Odysseus’ situation, alive or dead. Of course the ghost (the storyteller) has some fun at our expense, keeping us in suspense. No doubt Penelope needs to know, for her psychic health. But she also needs to know, as a pragmatic fact. There really are suitors for her, control over whom is crucial for the well-being of her house; and therefore whom she needs to keep aroused in their pursuit, whenever she appears to them. Bathing is not optional. Penelope needs to know Odysseus’ fate, so she can see what her options really are. May the best man win, sister.

In Greek:

‘As often as a lion changes his mind’: Homer in English