In the transmission of Homer’s music across time and economies, there is a lacuna that can only be filled by a sort of giant—a phase when giants walked the earth, common to many histories of the progress of civilisation around the world. Back of the itinerant thespian rhapsodes competing at city festivals around Greece, successive generations of anonymous wandering minstrels did not somehow, in increments, build a script of Homer, nor did orally improvising singer-songwriters and after-dinner citharodes. It seems that in between, behind a curtain, as yet unmasked, lived an extraordinary musical composer, steeped in bardic lays, but with the scale of vision to transform the meaning of ‘epic’ to include what can be found in an Iliad or an Odyssey. Not a tweaker of formulas, but a mysterious operatic Shake-Speare from beyond stage left, like the one who intruded into the rough mix of Elizabethan theatre.

There are grounds for an overhaul and a revolution in Homeric studies—entailing also a revolution in Homer’s reception, his public face. In particular we must reject many of the seemingly canonical oralist presumptions about the creation of Homer’s text, because of a shockingly fundamental oversight in its reading by modern authorities in democratic Classics.

The prejudices of the oralist mindset ignore wilfully the musical dimensions of the original composition that are both recorded and preserved in Homer’s Mediaeval manuscripts. Because of this, students and scholars have mistaken the libretto for the text, and have largely missed the music of Homer’s musical mix, with aria, dramatic recitative and lyric suspension in the midst of elemental catalogue narrative. Saving this verbal music from a debilitating ignorance will be critical for the transmission of Homer’s art to future generations. Homer’s poetry needs to be saved from both the tuneless metrics of the Classics departments and the primitive formulaic needs of the improvising bard, to be restored by skilled soloists to the theatre and even the concert stage. It is for these venues that Homer may plausibly be believed to have intended her compositions.

This music is not merely metrical (metre by itself is rarely sufficient for making music) but melodic and rhythmic. Generations of scholars and students have inexplicably ignored the accent marks that descend to us as essential features, not secondary diacritics, in the representation of Greek poetry (and prose) via alphabetic writing. In focusing solely on metre, and metrical phrasing as ‘building blocks’ that aid extemporisation in a supposedly improvised oral performance, Homeric studies have failed even to register the tonal and other musical effects that evidently inform and inspire Homer’s own aesthetic of the phrasal cadence and the dynamic line, in actual composition. This has led to an embarrassing and patronising blindness in Homer’s modern scholars, apologising for her repetitions with theories of formulaic composition—the bald opposite of the exquisite aural sensibility we may expect from the world’s most famous blind poet.

There is no royal road to the learning of ancient Greek. But with the newly discovered promise of performing the literature, afforded for the first time by a robust theory of ancient prosody, perhaps there will be a new attractant to those rare students capable of making headway in this most challenging and precious of humanist disciplines, who nowadays get what exposure they get through toneless translations into modern languages.

Let us forget what we think we know about ‘epic poems’. The phrase could etymologically be thought to describe products of ‘verbal music-craft’. ‘Formulas’ are therefore not germane: they are defined so as to be inherited, and come by the performer ready-made, not newly crafted; they are conceptualised for Homer, alone among Virgil, Dante, Milton and other proponents of the epic genre, as his means of filling up as yet vacant verses. Filler. The only craft required in the Homeric case would seem to be that of the jigsaw puzzle, in manufacture and use. Let us begin to think newly about the nature of Greek words and the musical dimensions of the poetic craft involved when a verbal pitch accent, expressed as built-in pitch contours, characterises the verbal material to be arranged and performed.

In the classical mainstream, however, we read:

… the competitive performances of the Homeric Iliad and Odyssey by rhapsodes at the Panathenaia were ‘musical’ only in an etymological sense, and the medium of the rhapsode was in fact closer to what we call ‘poetry’ and farther from to [sic] what we call ‘music’ in the modern sense of the word. Still, the fact remains that the performances of rhapsodes belonged to what is called the ‘competition [agōn] in mousikē’, just like the performances of citharodes (kithara-singers), citharists (kithara-players), auletes (aulos-players), and so on.1

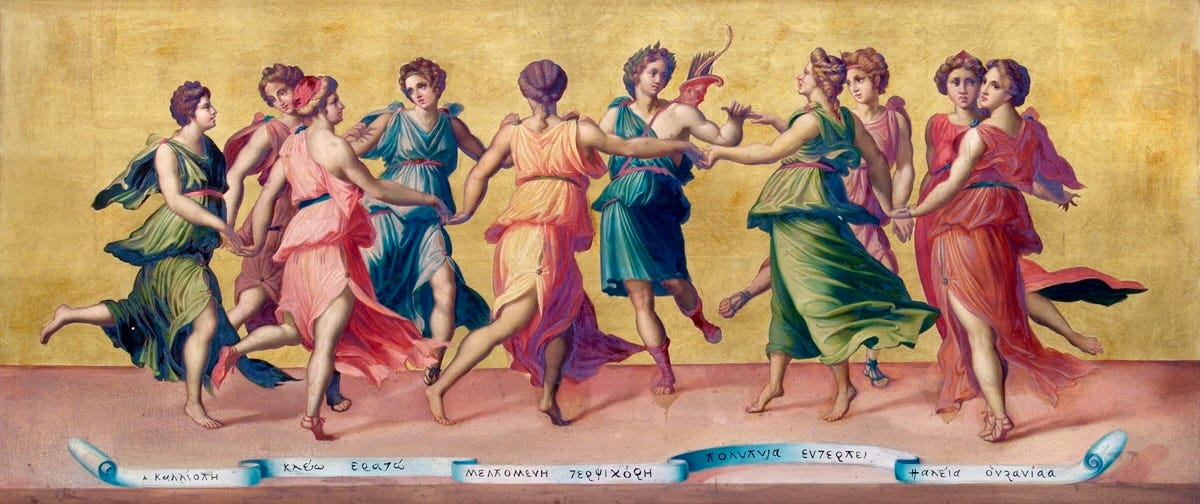

This claim about an ‘etymological sense’ is in fact completely backwards; it illustrates what can be lost in translation inside an academic culture that has lost awareness of circle dance traditions, along with their surrounding cultures, and applies literary standards to ancient genres once informed by dance. The Muses who give their name to μουσική, the ‘art of the Muses’, were dancers; on the occasions that they sang as well as danced, they would have had to sing rhythmically to suit their steps—keep time or stumble! Therefore it is the animation of dance rhythm that unites all the performers who competed ‘in μουσική’.

Rarely since the Renaissance do we find depictions where the Muses are actually dancing as though possessed—instead of languidly posed in intellectual reverie, too aristocratic to be good at their instruments. The ancient world is different, however. Consider the beginning of Hesiod’s Theogony. The Muses commission a singer to sing. It’s like a request of the DJ. They do sing as well, but what they are always doing is moving. They like to dance dactyls (elsewhere I give evidence from Plato and Aristotle that the phrase ‘dance of the Muses’, without further qualification, means one that beats out the seventeen steps of the dactylic hexameter.2) The Muses dance out the beat: the singer syncopates.

The modern semantic range of ‘music’ and ‘musical art’ raises the question why rhapsodes merely reciting Homer’s Muse’s song, could have been thought to compete in μουσική. This is not Aristotle’s problem! There is no controversy: the Homeric rhapsodes are Aristotle’s prime example in the list of dance-inspired arts. Consider Hesiod’s invocation of the Muses: the order of presentation is important. The end is Hesiod the solo poet with a special stick (like a rhapsode’s) which they gift to him when they breathe into him a divine voice (30-2). They do not dance around him, nor does he dance; but it seems somehow the effect of their song and presence is invested in the singer’s wand. It is the Muses’ dance, however, that comes first in Theogony’s hexameters, vigorously (3-8). They dance around Zeus’s altar, then bathe and establish ring dances (or dancing spaces) on Helicon. It is only when they start to move from there, under mist, that they send forth their voice and start hymning the gods (9-10). The song comes second. I presume they are still in rhythm, but no longer in a circle. It is also a presumption that the catalogue of deities they are described in Hesiod’s poem as hymning in the mist, in indirect discourse, doubles as and is identical to the actual hexameter hymn the Muses sang (11-21).

After becoming this invisible airborne song, the Muses inspire (literally) the singing voice in Hesiod. This moment is not without its metaphysics, despite the materiality of infused breath; I imagine some tactile prompt has been invested into the stick of laurel. Perhaps when he holds it he conjures their Heliconian dancing spaces, and they're real enough backbeat, in his mind. Certainly the singer in the centre feels ‘possessed’. (I have experienced this; see the video at http://danceofthemuses.info/homeric-dance.html.) It cannot be supposed that Hesiod keeps time to anything but the χορεία Μουσῶν, their ‘dance of the Muses’; that is, to the dactylic hexameter.

There is a parallel sequence at the banquet performance in the Odyssey’s Phaeacia. The nine selected boys—cross-dressed Muses?—start dancing first. Then Demodocus strums his phorminx in their midst and starts singing while they dance on. Later, Odysseus tells his wanderings without a lyre or dancers—a proto-rhapsode. The rhythm is a through-line in this phylogenetic development.

It is with this rhythm that the Muses possess and inspire a bard’s poetry, but also the divine soloists like Apollo, who sometimes stood in their midst playing the kithara, or Marsyas who competed with him on the flute, or the Pied Piper Dionysus. On this understanding it was the poet of the voice, and his dance-less performers the rhapsodes, who most purely and tightly expressed the rhythm of the Muses, and so the art μουσική; but dance rhythm surely informed the melodious instrumentalists as well. All of these rhythmic performers, it turns out, were ‘musical’ in the truly etymological sense.

Every line of Homer’s poetry is in a metre called the ‘dactylic hexameter’. This means that there are six dactyls, bum ba da, per line, with the last foot a shortened one. The generic rhythm, reinforced without syncopation, is:

Bum ba da bum ba da bum ba; da bum ba da bum ba da bum ba

In any given line it is the word accents and quantities that determine which syllables are tonally prominent, either rising or falling in pitch, so that a great variety of syncopations can result. Following the new theory of the Greek accent, the opening line of the Iliad,

μῆνιν ἄειδε θεά, Πηληϊάδεω ’Αχιλῆος

yields the following rhythm:

Bum ba da bum ba da bum; dum bum ba da bum ba da bum ba

(‘Bum’ is the thesis of the foot, ‘ba da’ the arsis; when a long substitutes for the two shorts of the arsis, I have said ‘dum’. Bold text signifies tonal prominence, either rising or falling in pitch.) This opening line is unusually regular: almost all the theses are reinforced accentually. Such ‘agreement’ is expected in the third thesis and the sixth—not required but expected in the aesthetic of the ancient pattern, with various kinds of ‘disagreement’ elsewhere in the line. The second line is quite syncopated in comparison:

οὐλομένην, ἣ μυρί’ Ἀχαιοῖς ἄλγε’ ἔθηκε

Bum ba da bum, dum bum ba da bum dum bum ba da bum ba

There is no cadence on the thesis of the third foot and a strong cadence in the arsis of the fourth (Ἀχαιοῖς), challenging the singer with an immediate return to a typical coda pattern for feet five and six (ἄλγε’ ἔθηκε) requiring adjacent stresses (Ἀχαιοῖς ἄλγε’). The third line, by contrast, cadences in the third foot but there is an effect of internal enjambment, as ἰφθίμους connects semantically to ψυχὰς in the fourth foot:

πολλὰς δ’ἰφθίμους ψυχὰς Ἄϊδι προΐαψεν

Bum dum bum dum bum dum bum ba da bum ba da bum ba

The striking solidity of consecutive long syllables is enlivened by the stress points; Ἄϊδι provides an anapaestic jolt.

The metre is a dance rhythm, for a particular dance of the Muses. The very word ‘foot’, inherited from the ancient world, suggests this rather obviously. Consider that the dactylic foot is perfectly balanced—the weak part is equivalent in time length to the strong part. This ‘isochrony’ in the foot is typical of dance rhythm, whereas speech-based poetic rhythms tend to have contrastive pulses, the weak part being shorter or less stressed than the strong part. (Aristotle alludes in his Poetics to the fact that normal Greek speech rhythm was in fact iambic in this sense, as is English speech.) Consider that most modern classical music, which is based explicitly on dance rhythms, also shows this time equivalence of the stressed and unstressed portions of the bar. There is also a living descendant of the ancient dactylic dances; the σύρτος is a round dance that is in fact the national dance of Greece. (It was performed as part of the closing ceremony at the Athens Olympics in 2004.) Here is a video that shows what it is like to dance a version of the modern σύρτος to Homer’s verses.

Note in particular the retrogression in each hexametric segment that breaks up the rightward motion, and how it corresponds to the characteristic word-breaks in the Homeric line.

How does a narrative take shape when it emerges from a musical medium of circling invocation? The celebrated salient peculiarities in the features of Homeric poetics—distinctive from the perspective of novels and modern literature—can all be seen to arise in the ambit of this question. How do the peculiar native features of an aesthetic of singing the names of people and things in lists, with a view to musical expression and rhythmic satisfaction, leave its imprint when the medium is adapted to the insertion of narratives? A modern investigator must begin by correcting his prejudice that Homer and Hesiod composed in a narrative medium: no, they created one, in a context where another aesthetic and other priorities were already in play.

One might compare these artists’ new emphasis to that of the attested invention of drama, out of the danced lyric presentation of myth in strophe and antistrophe, when one dancer from the circle first pretended to be a protagonist in the story, speaking his lines like an actor—and then two of them stepped out and rendered it into dramatic dialogue, transforming the choral medium into theatre and stealing the show. The modern researcher must consider Homer’s product in itself as a musical substance, prior to any attempt at narrative; this would seem to be the only way to avoid explaining away as oralisms the peculiar habit of melodic (‘metrical’) ‘naming phrases’ in Homeric and Hesiodic epic narrative, from the perspective of literary narrative, rather than the endemic musical habit of an accompanying singer’s technique, and flourish, in a medium designed for orchestic evocation.

The Homeric compositions are miracles of oratorio, a stylised melodic declaration which achieves an extraordinary realisation of narrative and lyrical expression, an achievement of sheer representation that is immediate, despite the fact that the medium of its pitch-accented art language is no longer alive. In the legacy of modern classical music, we find ourselves awash in such miracles. Like Bach’s oratorio, Homer’s is also grounded in, and infused by, the rhythms of dance.

No quantity of well-meaning liner notes filled with detailed historical biography has ever resolved, or even circumscribed, the miracle of musical composition. Just what was Mozart’s change of diet in Vienna that caused a change of favoured key? How proximate were Miles Davis’ most pointedly modal solos to injections of heroin? Modern Academia offers us Homeric poetry as a traditional product of an illiterate Dark Age, which left no archaeological, geological or literary strata. Parry’s theory utterly ignores the melodic substance recorded in our best manuscripts, which is precisely the substance that metre exists to serve. It is a complete travesty, a betrayal of the classicism that means to bring us forward the genius of Greek authors.

None of those classical authors, the original inheritors of Homer’s music saw fit to explain, or explain away, the irreducible genius of his craft, except perhaps with the rather ambivalent suggestion that the poet was blind. Whether the composer’s from Chios or Vienna, the music is the sound and the thing. It is disgraceful that Greek authors’ modern champions and defenders do not even attempt to sing the song of Homer, to try to register the experience of repeated melodic phrases, before filling introductory volumes of evidence-free verbiage in the way of wide-eyed students. Homer was the maverick who saw and seized the possibility, how the chanted bardic catalogue could become a one-man epic show.

A manuscript of Homer is like the Bach Cello Suites, which for generations existed only as fading marks on paper. As a musical score it harbours the possibility of being brought back to life, if, and only if, a performer can bring her own life and learning to the trick of its movement. Fear of ‘the genius’ and the ‘great man’ may yield at last to the truth about a sublime prehistoric composer, and the sublimity of her composed oratorio.

Gregory Nagy, ‘Epic’, in Richard Eldridge, ed., The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy and Literature, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009, 23.

David, The Dance of the Muses, 95-8.