Ἄνδρά μοι ἔννεπε, Μοῦσα, πολύτροπον, ὃς μάλα πολλά

πλάγχθη, ’πεὶ Τροίης ἱερὸν πτολίεθρον ἔπερσεν ·

πολλῶν δ’ ἀνθρώπων ϝἴδεν ἄστεα καὶ νόϝον ἔγνω,

πολλὰ δ’ ὅ γ’ ἐν πόντωι πάθεν ἄλγεα ὃν κατὰ θυμόν

ἀρνύμενος ἥν τε ψυχὴν καὶ νόστον ἑταίρων.

ἀλλ’ οὐδ’ ὧς ἑτάρους ἐρρύσατο, ἱέμενός περ·

αὐτῶν γὰρ σφετέρηισιν ἀτασθαλίηισιν ὄλοντο,

νήπιοι, οἳ κατὰ βοῦς Ὑπερίονος Ἠϝελίοιο

ἤσθιον· αὐτὰρ ὃ τοῖσιν ἀφείλετο νόστιμον ἦμαρ.

τῶν ἁμόθεν γε, θεά, θύγατερ Διός, ϝεἰπὲ καὶ ἡμῖν.

I hereby present first fruits of my mission to sing Homer: it amounts to a reaffirmation of the single articulated breath of the Homeric epos. I shall explain what I mean. The Homeric hexameter has a rich prehistory. It was born in a circle dance, emulating the newly stable paths of the sun’s outer planets with their regular retrogressions at opposition. (The leftward steps in the dance occurred from steps 9 to 12 of the 17, corresponding to the syllables between the trochaic caesura and the bucolic diaeresis.) It lent its rhythm to the chanting of catalogues, memorialising by bringing to orchestic life the list of ancestors and events that were shared in common by a people and a place. As these catalogues expanded internally, like a concertina, into episodic narratives, the hexameter’s story ends as a choice vehicle for epic narrative and drama, like the English pentameter. It persisted in this guise, somewhat remarkably, in the Latin language and the Roman era.

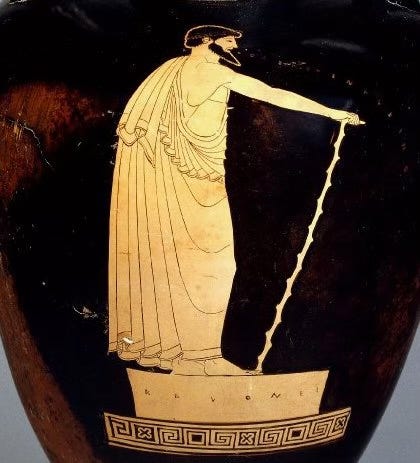

When I began this project, I tended to pause at what I have demonstrated to be a mid-line accentual cadence in Homer’s hexameter. This accentual cadence generates the two kinds of caesura in the third foot of the six. There is often a pause in sense at this location, and when one attempts to sing the pitch changes indicated in the score, a pause here is often welcome to separate the pitched rhythms before and after. In its history as a medium, the hexameter may well have observed a pause at mid-line, for example, in citharodic and other styles of melodic performance, including when using Homer’s verses. But I have become convinced by the texts we have that the Iliad and the Odyssey were composed for performance by a thespian rhapsode bearing a wand; and that in the composer’s hands the hexameter line had become a unit of expression—a single articulated breath. It was of course rhythmic and syncopated, and tonally inflected, but it was a single breath of speech. The articulation or articulations were phrasal, shaped by the pitch accent, but not necessarily requiring pauses. The necessary pause for breath was generally at line end, but I believe the performer’s freedom was comparable to a Shakespearean’s: a pause anywhere was permissible if it counted, and was always welcome at mid-line or at the diaeresis, if that worked better than at line end.

Stephen Daitz argued that the hexameter should be recited without a pause. I have given evidence that some lines in Homer seem to be scripted with a pause (in my new book, Singing Homer’s Spell, now available on Amazon, and soon in an Apple ebook complete with audio demonstrations). Yet I agree with Daitz about the integrity of the Homeric line in performance. It seems somehow to live in the consciousness of the performer, who will not breathe only at the end of each line, but when the lines and phrases themselves instruct him to. The orchestration of the breath is not beyond Homer’s scripting. That is a discovery about Homer’s stature and nature awaiting every Homeric performer! If Shakespeare has had his way with you, you will know what I mean: real verse sprung from a poet knows how to articulate itself.

Here, for now, is the opening of the Odyssey.

The Articulated Breath of Homer