How does one demonstrate that a musical text … is musical? It was one thing to demonstrate that the Linear B script was actually a representation of an historical stage of Greek. The decoded product was recognisable as Greek words and sentences, with minimal gibberish. While this was not true about other language candidates, the proof was not thereby achieved through a process of elimination; there was, rather, a positive identification, where Greek answered the decipherment internally with morphology and meaning, as well as recognisable proper names. It is also the case that Homer’s East Roman manuscripts preserve the location of the onset of Greek’s historical tonal contonation, and I have shown how this tonal contour reinforces a quantitative stress pattern first induced from the Homeric and other stichic Greek data by Allen. There is therefore a case to be made, and I have made it, for aesthetic choice in the placement of words in relation to Homeric metre, to reinforce ictus with accent in a patterned, syncopated way—neither automatic and monotonous nor purely random, but with expectations created of regular cadences, points of agreement at mid-line and line end.

Of course regular cadences are not the whole story of Homeric song, or any song worth remembering. But their presence establishes a sort of baseline, where Homeric verse is enough like other exemplars of authored narrative and dramatic verse, in Virgil or Dante or Milton or Shakespeare, that we should not be surprised to find the signs of dramatic life and even the authorial presence that we find insinuating and protruding throughout the musical art of these better understood composers.

When it comes to musicality, however, a certain reservation is made for taste and private experience. An impassioned and detailed case can be made for the perfection of a piece of music or its execution—the polyphonic sigh of a nocturne, or the consummation of a blues on the off-beat—but there will always be the fellow who wants to change the channel. It can be absurd, and often embarrassing to both parties, to try to explain how a certain favourite song is musical in some objectively delineatable way. Yet a Homerist has been reduced by a hundred years and more of metrical-traditional-oralist mumbo-jumbo, to being forced to prove there’s anything at all going on with his poet’s poetry, at any given moment, beyond filling up a hexameter line with a pre-fab building block of ‘traditional material’. People who felt the presence of a poet, along with unitarians generally, tended to be sneered at passive-agressively by the scientists.

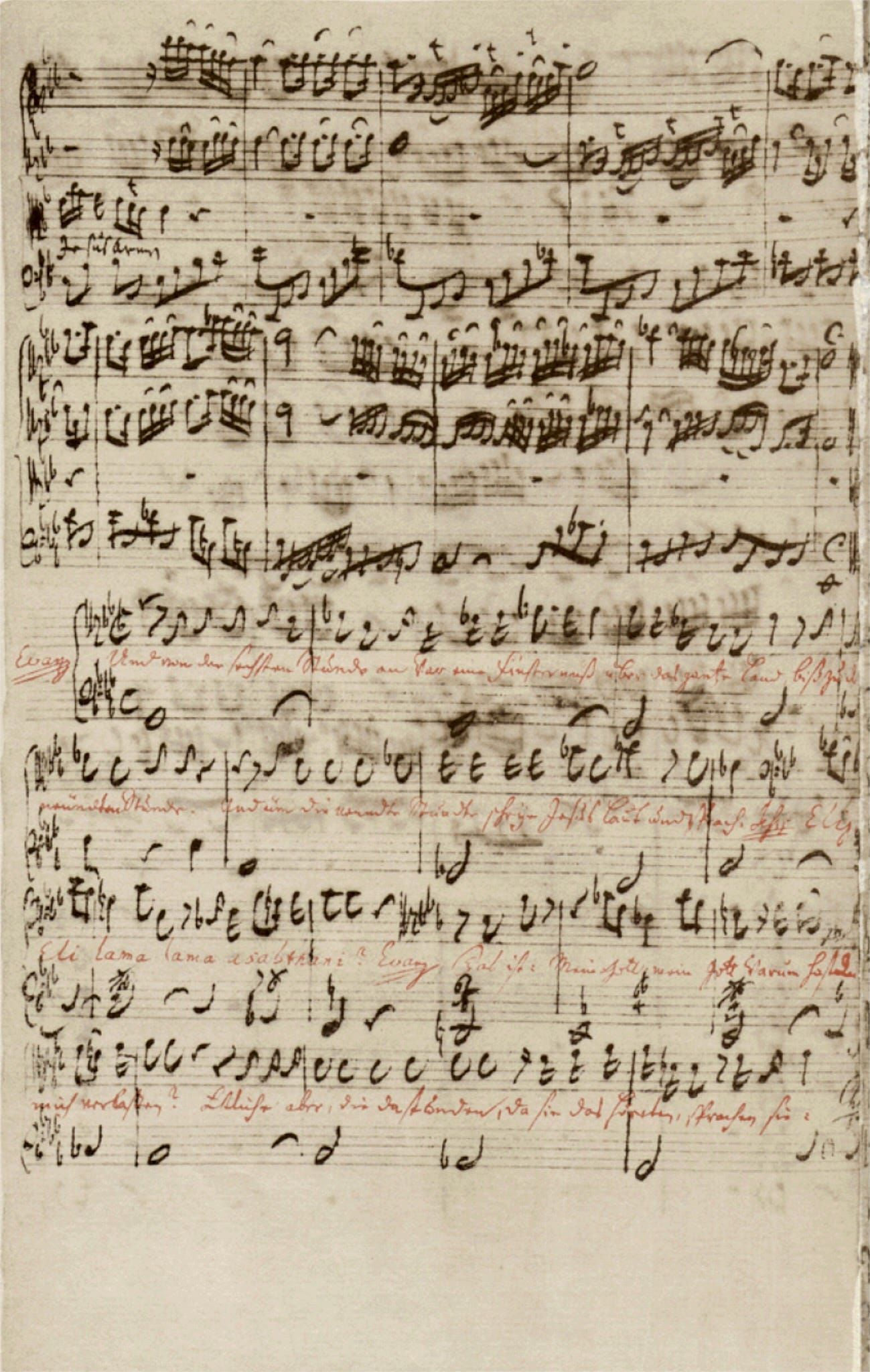

Consider the fate of an autograph of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion, were all knowledge to be lost about the significance of the staff or the patterns of dots and squiggles scrawled all over the pages. At what point would anyone consider looking beyond the fascinating story told there in German, seeing as that was (obviously) the actual text? Scholarship would proliferate, what with analysing the various diction and styles of the German script and speculating about its origins. No doubt some would argue that certain parts were ‘undoubtedly’ lyric poems or ‘arias’ originally separate from the Ur-text and later incorporated, while other parts, said to be by the so-called ‘M’ author, were believed to originate in some now lost unitary work, perhaps stemming from a German oral tradition—although a faction solidly maintains, citing parallel sources, that they bespoke a written original of this work, a sort of German ‘bible’. We envision a certain school that would be convinced that in the cyclic background, there were hints, still for them discernible at times in the St. Matthew Passion text, that the death of the Jesus figure was not in fact the end of it, as the extant text would have it, but that in some traditions it led to a transfiguring apotheosis of some kind. At what point would the project of deciphering the formulas in the squiggle patterns appeal to any but the most esoteric boundary riders in the academic club? Who could seriously think that such work could contribute anything worthwhile to the burgeoning anthropological debate on German Jesus-mythology, to which Picander (some say ‘M’, some even say ‘Bach’) contributes the fundamental text?

Now imagine what sort of lunatic it would be who dared claim that actually the staff and squiggles contained almost the whole point of the composition, and that the story being told was in large part a musical witnessing and a musical meditation. What chance would there be for the imagined music of Bach, on imaginary instruments and bodiless voices affected with longing, in the face of a mountain of linguistic and humanistic scholarship proliferating across generations about the textual transmission of a quasi-religious myth? ‘Hang on, this fellow is turning a foundational German text into a sort of Italian libretto. An unnecessary mystifier at best, at worst a mischievous self-aggrandiser. Yes of course there was music and dancing involved, everybody knows that. So what. Licence to teach denied!’

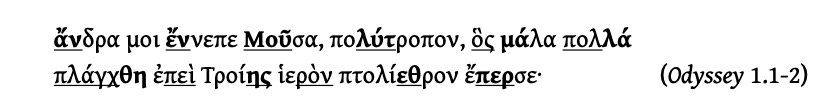

If the deciphering of Linear B was a momentous advance in our knowledge of the history of Greek, surely the discovery of the role of the pitch accent in epic and lyric was even more so, for the vivid understanding and experience of ancient Greek literature. We have long since known the feet, the sequence of dance steps encoded in the poems; now we know which syllables were dynamically reinforced, so we can hear for the first time how the natural rhythm in the words interacted with the ictus of the metre. Thus is revealed the run of the rhythm composed by the poet for these feet, as against the false automatic rhythm of the schoolboy, ignoring his legs and body and stressing the ictus (underlined) in his recitation:

Where the bold, accentually prominent syllable is not the same as the underlined syllable, or does not occur where there is one, there is musical disagreement between accent and ictus. In the sixth foot, I argue that accent determines ictus; my practice of underlining the sixth longum is to illustrate the variety of Homer’s final accentual cadences, contrasted with the Latin hexameter accentual cadence which is regular on the sixth longum. Homer’s lines often cadence on their final syllable—their final syllable is tonally prominent—unlike Virgil’s lines. There is shown to be a decisive variety in his compositional choices, in a position where the metrician records a ‘doubtful’ x, neither longum (⏤) nor breve (⏝) but ‘anceps’. In general, across Greek poetry, the metrician’s anceps is a secret sign for the initiated: at the middles and ends of periods, it strongly marks a locus of compositional interest and choice between qualities and locations of possible accentual cadence. But the confirmatory revelation here is regular agreement in the third foot near mid-line—bold text and underlining in the same syllable—which causes the two types of regular caesura, and is highlighted and offset by either a lack of reinforcement or outright disagreement in the syllables prior.

Why is this a revelation? Why is this disclosure about a prosodic landing point on the third downbeat of the hexameter, not simply a footnote to the usual, the pseudo-mathematical analysis by longums and breves (⏤⏝ x) of ancient poetry, into elaborate, static metrical patterns? Because it demonstrates a melodic and rhythmic motive in a context of purely musical desire, which dictates the choice and emplacement of words where they fulfil that desire. This is not word breaks causing ‘cuts’ in feet. It shows that there is a poet in the machine. He is not a trailing or revenant ghost, but a wilful intention speaking its purpose through the changes, in pitch and rhythm. These are not words fitted into schematics, but words punching and sliding and gracing their way among the beats of an hypnotic cycle. Homer and Penelope are inside there breathing out, like Odysseus tensed in the wooden horse, as surely as Hamlet lives in Hamlet.

The cadence pattern is ubiquitous. Stichic lines commonly tend to seek a mid-line cadence—perhaps to satisfy a feeling of balance, or the sense of passing a rhythmic fulcrum. The theory of the disyllabic contonation reveals Greek stichic verses to be no exception. The new theory now generates what had used to be an ad hoc metrical given in Homeric studies—the mid-line caesura, a supposedly ‘required’ word break in the middle of the third foot—as in fact a by-product of the purely musical desire to reinforce the metrical ictus near mid-line with tonal prominence. But this persistent musical desire, or pulse, finally serves a dramatic realisation and emergence that spills over into vitality, will and consciousness. This is a trick of all the great dramatic verse, but students and citizens can now see for themselves that Homer’s is no exception.

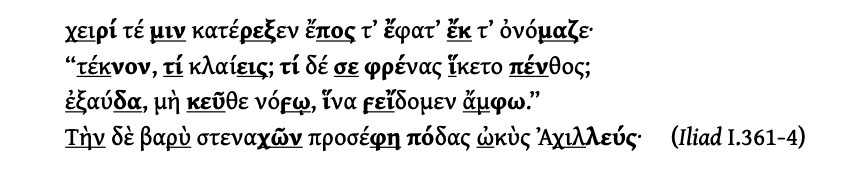

Here, for example, are some lines between Thetis and Achilles; all of them show agreement of accent and ictus, harmony and rhythm, boldface and underlining in the third foot—a third foot cadence causing caesura—preceded in the first two feet by a variety of disagreement and syncopation, including accent in the arsis, a lack of reinforcement, and also passing agreement. But in amongst this patterning, they capture and project a call to expression from a goddess, and a mamma’s boy’s groan in response:

She patted him on his arm, spoke a line and called it what it was:

‘Child, why are you crying? Why does sorrow reach you in your mind’s vessels?

Sound it out, don’t cover it up in thought—so we both may know.’

Groaning heavily he addressed her, Swift Foot Achilles:

ἐξαύδα: ‘Sound it out’ indeed. Each line divvies its phrases at different points—I find myself pausing at the mid-line word break, or caesura—a bit later in the case of 363, after νόϝῳ ‘in thought’—but in each line we find the regular third foot agreement (κατέρεξεν, κλαίεις, κεῦθε, στεναχῶν). In the first foot, however, there is no agreement at all (χειρί, τέκνον, ἐξαύ—, Τὴν δὲ). The initial ictus is not reinforced by tonal prominence. (There is a case for τέκνον being oxytone on the penult, in which case there is agreement here. I read barytone on the ultima, because of the comma following as well as the following consonant in τί.) It is as though each line blurs into focus midway, then cascades, lands and resolves—or stages a new departure at line end. The last line captures the wordless groan of Achilles in response, with a circumflected cadence on the omega of στεναχῶν, in our emended text courtesy of Gregory Nagy and the Byzantine Aristophanes. His name and epithet summon Achilles forward into the body of the rhapsode, as he readies for his mother his catalogue of grievances.

So many generations of readers and critics have approached verses like these without assessing or even registering their musical intention and sound: metre cannot do this by itself, in any species of musical analysis. One knows nothing of the music by knowing the vowel values and quantities: one needs to know also which syllables are pitched and stressed, and with which portion of the rising and falling contonation, and where these land in relation to the metrical beat. Then one can begin to sing them with purpose to a humanly sentient audience, and awaken them in sympathy to the indwelling presence of a protagonist. The field of Homeric line design is now wide open, as one moves on in one’s exploration to patterns of accentual reinforcement past the mid-line cadence causing the caesura, through to the retrogression, diaeresis and coda. But all these patternings serve their transgressions, caused (so it seems) by the presence of moved consciousness within the lines, and a directed gaze peering out.

The pattern of accentual reinforcement, disagreement moving to agreement at a mid-line cadence, is confirmed not only for the hexameter, but for the iambic trimeter as well. Here we have an ascending rhythm, and a metre not usually associated with singing but with the dramatic representation of speech. But the stichic pattern of the cadence at or near mid-line—common, it seems, to all languages that attempt a stichic line—is shown by the new theory of the Greek accent to be true of ancient Greek tragic verse as well. Whether its movement is descending dactylic or ascending iambic, the Greek poetic line is shown to be an human one after all, not some metaphysical combination of pure quantities and unrelated pitch modulations. This poetry had a beat, which was selectively reinforced by the tonally prominent syllables of its words. Once again, in the iambic trimeter, it is the musical motive for accentual reinforcement of a mid-line cadence that causes the various permutations of the tragic caesura. But the language of permutations and variety belong to the aerial survey: in each line down on the stage there is a definite choice and syncopation, which leaks out in these moments the thought, feeling and statement of Oedipus and Antigone and Clytemnaestra.

‘Emphasis’ is clearly a concept that bridges the realms of sound and meaning. Moments of rhythmic and harmonic emphasis are caused by the arrangement of words, enclitics, pauses and line ends, the last three of which can release the oxytones on the ultimas which would otherwise be suppressed as grave. It would be most strange, unthinkable really, that such composed musical moments could be irrelevant to the emphases in the unfolding of the narrative as such, or the rhetoric or emotion of a speech. Do all your favourite books on Homer and Pindar need to be rewritten in light of what their lines actually sound like as poetry? Well, yes—revisited at the very least. But my experience in reading secondary literature has been good, even though I’m the only one in the room, as it were, who’s actually heard the nuances and emphases of the original, as matters of sound. After applying my discoveries in performance for over thirty years, I find that critics generally have a sixth sense for what a poem is after; the musical touches and punches, along with enjambments and other weight-bearing loads, often support the arguments being made, in ways generally unknown—sometimes completely—to the scholar or student. It does not matter what lip service has been paid to framing theories or constructs like metrical oralism. It turns out critical insight comes from a sixth sense, it is not sparing. Musical facts tend to support published critical assertions about passages in Homer, even though they are thought by their authors to be grounded somehow in the various prevalent dogmas, or in a beat-less quantitative poetic fantasy. It would be good, however, if critical observations were grounded, to begin with and first and foremost, in the objective musical phenomena reflective of a poet’s compositional choices. The new theory of the accent can allow this.

This new theory is a development in the field of Classical languages comparable to the introduction of the law F=ma in classical physics. That is because there is not an interaction with a classical text that does not depend on one’s interpretation of emphasis, and it is impossible to read this emphasis without knowing how language is actually accented in performance. In point of fact, one cannot even talk without knowing this, let alone compose or recite poetry. The law of tonal prominence must therefore be promulgated for the use, abuse, and inspiration of students of the ancient world.

Yet no one invites me to teach what I can show. While I am alive, this fact must unfortunately intrude as a significant part of the story. Despite the publication of my first book, no Classics department has seen fit to call me back for an interview, let alone appoint me to guide students or advance this work with colleagues. One hears no whisper of a ‘David’s Law of Tonal Prominence’ for Greek and Latin. This puts me in a somewhat ridiculous and sad position. Without institutional support, one is a carnival barker.

The only one in the room! My first book was published in 2006 by Oxford. I had reason to think that ignoring it was not an option, when it was presented in such a venue. I am now disabled in my sixtieth year, and with no lack of merit or recommendation from my teachers, I have had no chance to follow my vocation to teach Greek, no opportunity to explore with dedicated students this material suddenly opened up vast and new, nor to advance the project I began in the early 2000s, with choreographer Miriam Rother, reconstructing Sophoclean and Aeschylean choruses with students from St. John’s College. Institutions no doubt find my résumé suspicious, though I have done literally nothing to create a reputation except publish my findings. We have discovered a treasure of more importance and impact than that uncovered in Tutankhamen’s tomb! We now have the key to unlock the interpretation and performance of all the ancient Greek poets, the key to a poetic treasury hidden in plain sight, a legacy of music and drama and epic more valuable than all Tutankhamen’s gold.

One can have no illusions about this discovery’s importance to every class of Greek or Latin attempted since. Yes it does matter, if you want to speak about what a poem says, or call such a poem a ‘tragedy’ or ‘choral lyric’ or ‘epic’, or other ancient words that also demand discussion and explanation, that you first become familiar with the rhythm and tonal cadence which give its meaning a colour and a sound. The consummation and reward of all analysis is in bringing the score to life. It would seem that there may be authorities in the field who would prefer that the meaning of Homer’s request of the Muse to sing remains a mystery, circumscribed by certain parameters that allow the production of scholarly papers on the question. Crucially, such papers do not resolve a ‘productive’ mystery that keeps the journals and their contributors busy in business. But there is no mystery to the clarion song of Homer at all. Instead, evidence in plain sight has been misinterpreted or ignored. We have but to breathe and sing. The mystery has always been not with the song but with its source.

This will not be admitted, but the concept of ‘oral tradition’ was always meant to replace the Muses. 20th Century colonialist rationalism was seduced and bewitched by this sort of claim about the ultimate source of the poems. The Muse was made a statue and put in a museum. But oral theory proposes not only the source of the Nile; in our hubris we saw there a theory of the composing of the Ocean. The hexameter itself became hypostasised as a slave master who forced the creation of new diction and the development and use of reusable formulas to fit his arbitrary constraints.

We instead restore the musical motives that propel the line as an enthusiastic accompanist to the beat of a real round dance. We are intimate with such cadences and altered diction in our song lyrics; rock singers need to fetishise the word ‘baby’ as much for its beat, with unnatural lengthening and emphasis as needed, as for its typing of women. We can explain the origin of caesura and diaeresis in Homeric music, through accompanying and enhancing the peculiar form of a turning dance, but we do not yet explain why Homer’s music sounds different from Hesiod’s accompaniment to the dance of the Muses, nor do we touch on origins in describing this music’s composition. One may get to find oneself in the same room as Homer’s song, but the Muse remains numinous in one’s presence and minds her own company. The best clue we have about her is that she is a natural dancer, before she is a singer of Greek.